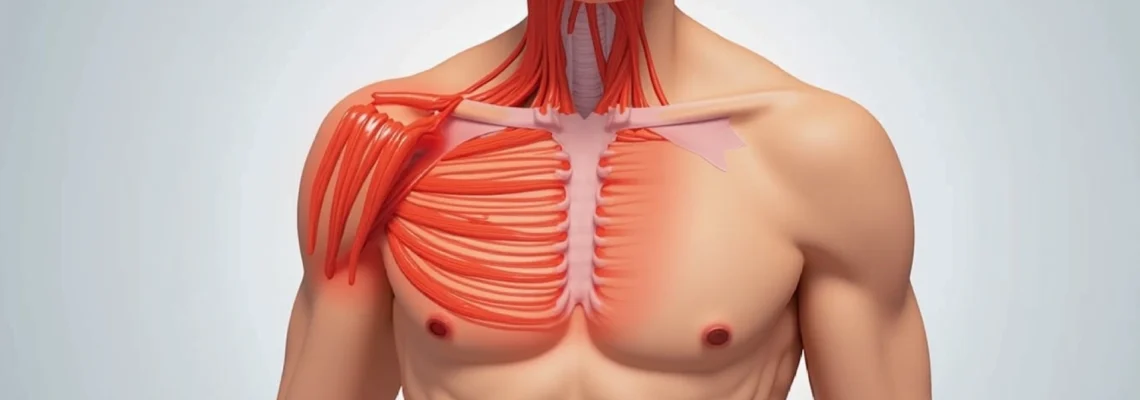

Pectoral pain radiating towards the axillary region represents a complex clinical presentation that can stem from numerous anatomical structures and pathophysiological processes. The intersection of muscular, lymphatic, vascular, and neurological systems in this anatomical area creates a diagnostic challenge for healthcare professionals. Understanding the multifaceted nature of axillary pectoral pain requires comprehensive knowledge of regional anatomy, coupled with systematic evaluation approaches that can distinguish between benign musculoskeletal conditions and potentially serious underlying pathologies.

The axillary region serves as a critical anatomical crossroads where the chest wall, shoulder girdle, and upper extremity converge. This convergence zone contains vital structures including the pectoralis major insertion, intercostal muscles, lymphatic drainage pathways, and complex neurovascular bundles. When pain develops in this region, it can significantly impact daily activities and quality of life, making accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment paramount for optimal patient outcomes.

Musculoskeletal causes of axillary pectoral pain

Musculoskeletal disorders represent the most common aetiology of pectoral pain extending into the axillary region. These conditions typically arise from mechanical stress, overuse patterns, or acute traumatic events affecting the complex muscular architecture surrounding the shoulder girdle and chest wall. The interconnected nature of these muscle groups means that dysfunction in one area can create compensatory patterns leading to pain referral into adjacent regions.

Pectoralis major strain and insertion tendinopathy

Pectoralis major injuries constitute a significant proportion of exercise-related chest wall pain, particularly among athletes engaged in weightlifting, swimming, or contact sports. The muscle’s broad insertion along the lateral lip of the bicipital groove creates a vulnerable transition zone where mechanical stress concentrates during forceful adduction and internal rotation movements. Grade I strains typically present with mild pain during specific movements, whilst Grade II injuries involve partial muscle fibre disruption with associated swelling and functional limitation.

Complete pectoralis major ruptures, though rare, create distinctive clinical presentations including visible muscle deformity, sudden onset severe pain, and immediate functional loss. The characteristic “pop” sensation followed by rapid swelling and bruising helps differentiate complete tears from minor strains. Early recognition becomes crucial as delayed surgical intervention can compromise functional outcomes, particularly for athletes requiring high-level performance.

Intercostal muscle inflammation and trigger points

Intercostal muscle dysfunction frequently manifests as sharp, stabbing pain that follows the rib contours and may radiate anteriorly toward the axilla. These thin muscle layers between adjacent ribs can develop myofascial trigger points following respiratory infections, prolonged coughing episodes, or repetitive rotational activities. The pain pattern often demonstrates a dermatomal distribution, creating confusion with neurological conditions.

Trigger point referral from intercostal muscles creates a particularly challenging diagnostic scenario. Active trigger points in the lateral intercostal spaces can generate pain that extends into the axillary fold, mimicking cardiac or pulmonary pathology. Palpation techniques targeting specific intercostal spaces help differentiate muscular pain from visceral referred pain patterns.

Serratus anterior dysfunction and winged scapula syndrome

The serratus anterior muscle’s strategic position along the lateral chest wall makes it susceptible to overuse injuries in overhead athletes and manual labourers. Long thoracic nerve dysfunction can create secondary serratus anterior weakness, leading to compensatory pectoralis major overactivation and subsequent axillary pain development. This muscular imbalance creates altered scapulohumeral mechanics that perpetuate pain cycles.

Winged scapula presentation varies from subtle prominence to obvious medial border elevation during wall push-off testing. The associated anterior chest wall discomfort often extends into the axillary region as accessory muscles attempt to stabilise the shoulder girdle. Progressive exercises targeting serratus anterior strengthening typically resolve symptoms, though recovery timelines vary based on underlying nerve involvement severity.

Costochondral junction irritation and tietze syndrome

Costochondritis affecting the lateral costochondral junctions can create pain referral patterns extending into the axillary region. Unlike typical costochondritis affecting the sternocostal joints, lateral costochondral irritation often results from repetitive chest expansion activities or direct trauma to the lateral chest wall. The pain typically worsens with deep inspiration, coughing, or trunk rotation movements.

Tietze syndrome represents a distinct entity characterised by visible swelling at affected costochondral junctions combined with localised tenderness. The inflammatory process can extend beyond the immediate junction area, creating diffuse chest wall pain that radiates toward the axilla. Conservative management with anti-inflammatory medications and activity modification typically provides symptom resolution within several weeks.

Lymphatic and vascular disorders affecting the axillary region

The axillary region houses the largest concentration of lymph nodes in the upper extremity, making it susceptible to various lymphatic disorders that can present as localised pain or discomfort. Vascular complications, though less common, can create serious conditions requiring immediate medical attention. Understanding the complex interplay between lymphatic drainage patterns and vascular supply helps clinicians identify potentially serious underlying conditions.

Lymphadenopathy and reactive lymph node enlargement

Axillary lymphadenopathy commonly develops as a reactive process following upper extremity infections, recent vaccinations, or systemic inflammatory conditions. Enlarged lymph nodes can create localised pressure effects that manifest as axillary discomfort extending into the adjacent pectoral region. The pain quality typically differs from muscular pain, often described as a deep aching or pressure sensation rather than sharp, movement-related discomfort.

Infectious lymphadenitis can progress rapidly, creating significant axillary swelling accompanied by erythema and systemic symptoms. Bacterial lymphadenitis requires prompt antibiotic intervention to prevent abscess formation or cellulitis spread. Viral-induced lymph node enlargement typically resolves spontaneously but may persist for several weeks following the initial infectious episode.

Axillary vein thrombosis and Paget-Schroetter syndrome

Primary axillary vein thrombosis, also known as Paget-Schroetter syndrome or “effort thrombosis,” typically affects young, active individuals following repetitive overhead activities. The condition results from compression of the axillary-subclavian vein complex between the first rib and clavicle during arm elevation. Initial symptoms include axillary pain, arm swelling, and prominent superficial venous collaterals.

Early recognition becomes critical as delayed treatment can lead to chronic venous insufficiency or post-thrombotic syndrome. Diagnostic imaging with venous duplex ultrasonography or venography confirms the diagnosis, whilst treatment typically involves anticoagulation followed by possible thrombolytic therapy or surgical decompression depending on symptom severity and chronicity.

Thoracic outlet syndrome with neurovascular compression

Thoracic outlet syndrome encompasses a spectrum of conditions involving compression of neurovascular structures within the thoracic outlet. Neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome, the most common variant, can create axillary pain combined with upper extremity numbness, tingling, and weakness. The pain often intensifies with overhead activities and may extend from the neck down into the axillary region.

Provocative testing including Adson’s test, Wright’s test, and the elevated arm stress test help identify neurovascular compression patterns.

The complexity of thoracic outlet syndrome diagnosis requires comprehensive evaluation of symptoms, physical examination findings, and objective testing results to distinguish it from other conditions affecting the shoulder girdle.

Treatment approaches range from conservative physical therapy to surgical decompression based on symptom severity and functional impact.

Hidradenitis suppurativa and axillary abscess formation

Hidradenitis suppurativa represents a chronic inflammatory condition affecting apocrine gland-rich areas including the axillae. The condition creates recurrent painful nodules, abscesses, and ultimately sinus tract formation that can extend into the lateral chest wall. Early stages may present as simple axillary pain or discomfort that progresses to more obvious inflammatory lesions.

Acute axillary abscesses can develop from various causes including infected hair follicles, sebaceous cysts, or secondary bacterial infection of compromised skin integrity. The associated pain often radiates into the adjacent pectoral region due to inflammatory mediator release and tissue oedema. Prompt surgical drainage combined with appropriate antibiotic therapy prevents progression to necrotising fasciitis or systemic sepsis.

Cardiac and thoracic pathologies presenting as axillary pain

Cardiac conditions can manifest as axillary pain through complex referred pain mechanisms involving shared neural pathways between cardiac sympathetic innervation and somatic sensory fibres supplying the upper extremity and chest wall. Atypical presentations of cardiac ischaemia may predominantly feature axillary discomfort rather than classic substernal chest pain, particularly in women, elderly patients, and individuals with diabetes mellitus.

Myocardial infarction presenting with isolated axillary pain represents a diagnostic challenge that requires high clinical suspicion and appropriate cardiac evaluation. The pain may be described as a deep aching or pressure sensation that differs qualitatively from typical anginal symptoms. Associated symptoms including nausea, diaphoresis, dyspnoea, or unexplained fatigue should prompt immediate cardiac assessment even when chest pain remains absent.

Pericarditis can create referred pain patterns extending into the axillary region, particularly when the lateral pericardial surfaces become inflamed. The characteristic positional component of pericarditic pain, typically worsening with recumbency and improving with forward leaning, helps differentiate it from other causes of axillary discomfort. However, atypical presentations may lack these classical features, requiring electrocardiographic evaluation and inflammatory marker assessment.

Aortic dissection, though rare, can present with axillary pain as the initial symptom when the dissection extends into the arch vessels or creates differential pressures between upper extremities. The pain typically demonstrates an abrupt onset with maximal intensity at symptom initiation, contrasting with the crescendo pattern typical of acute coronary syndromes. Pulse deficits or blood pressure differences between arms may provide additional diagnostic clues, though these findings are not universally present.

Pulmonary embolism can occasionally manifest with axillary pain, particularly when involving peripheral pulmonary vessels near the pleural surfaces. The associated pleuritic component typically worsens with deep inspiration, whilst concurrent dyspnoea, tachycardia, or hypoxaemia suggest pulmonary vascular involvement. Risk factor assessment including recent immobilisation, surgery, or underlying thrombophilic conditions helps guide diagnostic evaluation.

Neurological conditions causing referred axillary discomfort

Neurological causes of axillary pectoral pain encompass a diverse range of conditions affecting different levels of the nervous system, from central pathways to peripheral nerve entrapments. The complex innervation patterns of the axillary region create opportunities for referred pain from distant neurological structures, making comprehensive neurological evaluation essential when musculoskeletal causes have been excluded.

Brachial plexus neuritis and Parsonage-Turner syndrome

Brachial plexus neuritis, also known as Parsonage-Turner syndrome, typically presents with sudden onset severe shoulder and axillary pain followed by progressive weakness in affected muscle groups. The initial pain phase can be excruciating, often described as burning or electric in quality, and may persist for days to weeks before weakness becomes apparent. The condition frequently follows viral infections, vaccinations, or surgical procedures, though many cases remain idiopathic.

The evolution from pain to weakness creates a characteristic clinical pattern that helps distinguish brachial plexus neuritis from other neurological conditions. Serratus anterior weakness commonly develops, creating the secondary effects described in earlier sections. Recovery typically occurs over months to years, though some patients experience persistent deficits depending on the extent of axonal damage versus demyelination.

Cervical radiculopathy with C5-C6 nerve root involvement

Cervical radiculopathy affecting the C5 or C6 nerve roots can create referred pain extending into the axillary region through dermatomal and myotomal distribution patterns. Disc herniation, foraminal stenosis, or spondylotic changes commonly affect these nerve roots, creating both sensory and motor symptoms that may be misinterpreted as local shoulder pathology.

The pain distribution typically follows anatomical patterns, with C5 radiculopathy affecting the lateral shoulder and upper arm, whilst C6 involvement extends into the thumb and index finger. However, overlap between dermatomes can create atypical presentations where axillary pain predominates. Provocative manoeuvres including Spurling’s test help identify cervical spine involvement, though imaging correlation remains necessary for definitive diagnosis.

Long thoracic nerve palsy and accessory nerve dysfunction

Isolated long thoracic nerve palsy can develop following surgical procedures, repetitive overhead activities, or blunt trauma to the lateral chest wall. The resulting serratus anterior weakness creates altered scapular mechanics that may manifest as anterior chest wall or axillary discomfort rather than obvious winging. The pain typically develops gradually as compensatory muscle patterns emerge.

Spinal accessory nerve dysfunction affecting trapezius function can create similar compensatory patterns that ultimately manifest as axillary pain. The complex interplay between trapezius weakness, altered scapular positioning, and secondary muscle overactivation creates persistent discomfort that may not obviously relate to the initial nerve injury.

Understanding these compensatory pain patterns helps clinicians identify the true underlying pathology rather than treating secondary symptoms in isolation.

Median and ulnar nerve entrapment syndromes

Proximal median nerve entrapment, though less common than carpal tunnel syndrome, can occur at several anatomical locations including the pronator teres or anterior interosseous nerve branches. These entrapments may create referred pain extending proximally into the axillary region, particularly when associated with inflammatory changes or space-occupying lesions.

Ulnar nerve compression at the cubital tunnel or Guyon’s canal can similarly create proximal pain referral patterns that extend into the axillary region. The associated paraesthesiae typically follow classic ulnar distribution patterns, though isolated pain referral without obvious sensory symptoms can occur. Nerve conduction studies help localise entrapment sites and quantify severity when clinical examination findings remain equivocal.

Oncological considerations in axillary pectoral pain assessment

Malignant processes affecting the axillary region can present with insidious pain development that may be initially attributed to benign musculoskeletal conditions. Primary soft tissue sarcomas, metastatic lymphadenopathy, and haematological malignancies represent serious conditions that require early identification and appropriate oncological referral. The challenge lies in distinguishing between benign reactive lymphadenopathy and pathological lymph node enlargement based on clinical presentation alone.

Breast cancer frequently metastasises to axillary lymph nodes, creating the potential for axillary pain as an early presenting symptom. However, early-stage breast cancer rarely causes pain, making other concerning features such as palpable masses, skin changes, or nipple discharge more reliable indicators of malignancy. The combination of axillary lymphadenopathy with suspicious breast findings warrants urgent breast imaging and surgical evaluation.

Lymphomas, particularly Hodgkin lymphoma, can present with axillary lymphadenopathy accompanied by systemic symptoms including fever, night sweats, and unintentional weight loss. The lymph nodes may demonstrate characteristic features including firm consistency, fixed adherence to surrounding tissues, and progressive enlargement over time. Pain is not typically prominent in lymphomatous lymphadenopathy, making its presence more suggestive of inflammatory or infectious aetiology.

Primary bone tumours or metastatic disease affecting the ribs, clavicle, or proximal humerus can create axillary pain through local tissue invasion or pathological fracture risk. The pain typically demonstrates a progressive pattern that worsens over time and may be accompanied by constitutional symptoms or evidence of systemic disease. Imaging evaluation becomes essential when clinical suspicion exists, with initial plain radiographs followed by advanced imaging modalities as indicated.

Diagnostic imaging protocols and clinical examination techniques

Comprehensive evaluation of axillary pectoral pain requires systematic clinical examination combined with appropriate imaging modalities selected based on suspected underlying pathology. The clinical examination should begin with detailed history taking, focusing on pain characteristics, temporal patterns, aggravating and alle

viating factors, and associated symptoms.

Physical examination should systematically assess the axillary region through inspection, palpation, and functional testing. Visual inspection may reveal obvious swelling, erythema, or anatomical asymmetry that provides immediate diagnostic clues. Palpation techniques should target specific anatomical structures including lymph nodes, muscle bellies, and bony prominences whilst noting tissue temperature, consistency, and tenderness patterns. Range of motion testing helps identify mechanical restrictions and reproducing pain patterns that correlate with suspected diagnoses.

Ultrasound imaging represents the initial imaging modality of choice for axillary region evaluation, providing real-time visualisation of soft tissue structures without radiation exposure. High-frequency transducers can differentiate between solid masses, cystic lesions, and vascular abnormalities whilst enabling guided biopsy procedures when indicated. Doppler evaluation adds valuable information about vascular flow patterns and can identify thrombotic complications or inflammatory hyperaemia.

Magnetic resonance imaging becomes essential when complex soft tissue pathology is suspected or when ultrasound findings require further characterisation. MRI provides superior contrast resolution for evaluating muscle injuries, nerve compression syndromes, and occult inflammatory conditions. The multiplanar imaging capability allows comprehensive assessment of anatomical relationships that may not be apparent on other imaging modalities.

Computed tomography serves specific roles in axillary region evaluation, particularly when bony abnormalities are suspected or when contrast-enhanced vascular imaging is required. CT angiography can identify vascular compression syndromes or thrombotic complications with excellent spatial resolution. However, the radiation exposure limits its use as a first-line imaging modality, particularly in younger patients or those requiring serial examinations.

The key to successful diagnosis lies in correlating clinical presentation with appropriate imaging findings, recognising that normal imaging does not exclude significant pathology when clinical suspicion remains high.

Electrodiagnostic testing including nerve conduction studies and electromyography provides objective assessment of neurological function when nerve-related pathology is suspected. These studies can localise specific nerve lesions, quantify severity, and differentiate between demyelinating and axonal injury patterns. The timing of electrodiagnostic testing becomes critical, as acute nerve injuries may not demonstrate abnormalities until several weeks after symptom onset.

Laboratory evaluation should be tailored to clinical suspicion, with inflammatory markers including erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein helping identify systemic inflammatory conditions. Complete blood count abnormalities may suggest haematological malignancies, whilst specific tumour markers become relevant when oncological conditions are suspected. Microbiological cultures from any drainage or aspirated material help guide antibiotic selection for infectious processes.

Advanced imaging techniques including positron emission tomography may be required for staging malignant conditions or identifying metabolically active inflammatory processes. However, these modalities should be reserved for specific clinical scenarios where conventional imaging and laboratory evaluation have not provided adequate diagnostic information. The integration of multiple diagnostic modalities often becomes necessary to establish definitive diagnoses in complex cases.

The diagnostic approach must remain flexible and responsive to evolving clinical presentations, recognising that initial working diagnoses may require modification based on treatment response or additional diagnostic information. Serial examinations and repeat imaging may be necessary when symptoms persist or progress despite appropriate initial management. This systematic approach ensures comprehensive evaluation whilst avoiding unnecessary testing and associated healthcare costs.