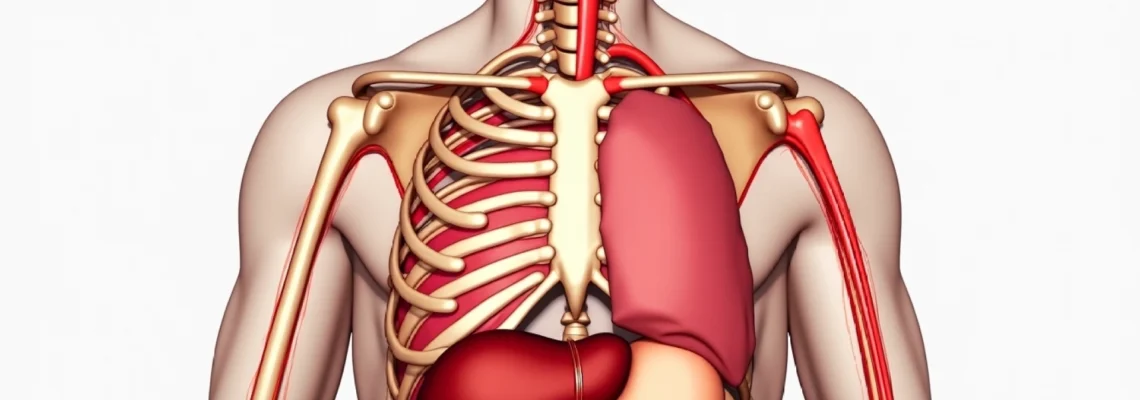

Pain beneath the central rib cage represents one of the most challenging diagnostic puzzles in clinical medicine, affecting millions of individuals worldwide. This anatomically complex region houses critical organs including the stomach, pancreas, liver, and gallbladder, whilst simultaneously serving as the attachment point for numerous muscles, cartilages, and neural pathways. The epigastric area , as medical professionals term this region, frequently becomes the focal point of diverse pathological processes that can range from benign muscular strain to life-threatening cardiovascular emergencies. Understanding the intricate causes of sub-costal pain requires a comprehensive examination of anatomical structures, physiological processes, and the myriad conditions that can disrupt normal function in this vital area of the human body.

Anatomical structure of the epigastric and hypochondriac regions

The epigastric region, positioned directly below the xiphoid process and extending laterally to encompass portions of the hypochondriac areas, represents a convergence point where multiple anatomical systems intersect. This area spans approximately from the sixth intercostal space superiorly to the subcostal margin inferiorly, creating a complex three-dimensional space where thoracic and abdominal cavities meet. The anatomical complexity of this region explains why pain localisation can prove particularly challenging for both patients and healthcare providers.

Xiphoid process and costal cartilage positioning

The xiphoid process, the smallest and most inferior portion of the sternum, serves as a crucial anatomical landmark for understanding epigastric pain patterns. This cartilaginous structure, which typically ossifies during middle age, provides attachment points for the rectus abdominis muscle and the diaphragm’s central tendon. Xiphoid process inflammation , known as xiphoidalgia, can create persistent, localised pain that patients often describe as a sharp, stabbing sensation directly beneath the breastbone.

The costal cartilages of ribs seven through ten create the costal margin, forming the lower boundary of the thoracic cage. These flexible structures allow for respiratory expansion whilst protecting underlying organs. When these cartilages become inflamed or injured, they can generate significant sub-costal pain that may radiate across the epigastric region, often mimicking more serious intra-abdominal pathology.

Diaphragmatic attachment points and intercostal muscle distribution

The diaphragm’s peripheral attachments to the lower six ribs and their cartilages create potential sites for referred pain patterns. Diaphragmatic irritation, whether from inflammatory processes or mechanical dysfunction, frequently manifests as epigastric discomfort. The phrenic nerve, which innervates the diaphragm, can transmit pain signals that patients perceive as originating from the upper abdomen rather than the actual source of irritation.

Intercostal muscles spanning the rib cage contribute significantly to respiratory mechanics and postural stability. These muscles, when strained through excessive coughing, lifting, or sudden movements, can create persistent aching sensations beneath the ribs. Intercostal muscle strain often presents with characteristic pain that worsens with deep inspiration or trunk rotation, helping differentiate it from visceral causes of epigastric pain.

Visceral organ proximity: stomach, liver, and pancreatic positioning

The anatomical positioning of major visceral organs creates complex patterns of referred pain that can confound clinical diagnosis. The stomach’s fundus extends superiorly beneath the left hemidiaphragm, whilst the antrum and pylorus occupy the central epigastric region. This positioning means that gastric pathology often presents with pain directly beneath the xiphoid process, though the intensity and character can vary significantly depending on the underlying condition.

The liver’s substantial mass occupies the right hypochondriac region, extending across the midline in many individuals. Hepatic pathology, including hepatomegaly or inflammatory conditions, commonly generates pain that radiates from the right upper quadrant across the epigastric area. Similarly, the pancreas, nestled deep within the retroperitoneum, can produce profound epigastric pain that frequently radiates to the back, creating the classic “boring” sensation characteristic of pancreatic pathology.

Neurovascular bundle pathways through the lower thoracic wall

The intercostal neurovascular bundles, comprising arteries, veins, and nerves, travel along the inferior aspect of each rib within the costal groove. These structures are particularly vulnerable to compression or irritation, especially in conditions affecting rib mobility or posture. Intercostal neuralgia can produce sharp, shooting pains that follow specific dermatomal patterns, often creating confusion with visceral pain sources.

The sympathetic nervous system’s thoracic splanchnic nerves converge in the celiac plexus, creating a complex network that innervates multiple abdominal organs. This anatomical arrangement explains why epigastric pain can seem disproportionate to the actual pathology and why emotional stress can significantly influence pain perception in this region.

Gastrointestinal disorders causing Sub-Costal pain syndromes

Gastrointestinal pathology represents the most common source of epigastric pain, encompassing a broad spectrum of conditions that range from functional disorders to serious inflammatory diseases. The rich nerve supply to digestive organs means that even minor disruptions in normal physiology can produce significant discomfort. Understanding these conditions requires recognition of their distinct pain patterns, associated symptoms, and temporal relationships to meals or specific triggers.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and hiatal hernia complications

GERD affects approximately 20% of the population in developed countries, making it one of the most prevalent causes of epigastric discomfort. The condition occurs when stomach acid regularly flows back into the oesophagus, creating inflammation and characteristic burning sensations. Epigastric pain from GERD typically presents as a burning or aching sensation that worsens after meals, particularly when consuming acidic or fatty foods.

Hiatal hernias, present in up to 60% of individuals over age 60, can significantly exacerbate GERD symptoms. When portions of the stomach herniate through the diaphragmatic hiatus, normal lower oesophageal sphincter function becomes compromised. This anatomical disruption often produces a characteristic pattern of epigastric pain that worsens when lying flat or bending forward, as these positions facilitate acid reflux.

The relationship between hiatal hernias and epigastric pain extends beyond simple acid reflux. Large hiatal hernias can create mechanical compression effects, leading to early satiety and a sensation of fullness beneath the ribs. Some patients describe feeling as though food becomes “stuck” in the epigastric region, particularly when consuming solid foods or eating rapidly.

Peptic ulcer disease: duodenal and gastric ulcer manifestations

Peptic ulcer disease, affecting approximately 10% of the global population at some point in their lives, creates distinct patterns of epigastric pain that can aid in differential diagnosis. Gastric ulcers typically produce pain that worsens immediately after eating, as food stimulates acid production and comes into direct contact with the ulcerated gastric mucosa. This pain often localises to the left of the epigastric midline and may be accompanied by early satiety and weight loss.

Duodenal ulcers, conversely, often improve temporarily with food intake as meals help neutralise excess stomach acid. However, duodenal ulcer pain characteristically returns two to four hours after eating, often waking patients from sleep during the early morning hours. This cyclical pattern of pain relief and recurrence helps distinguish duodenal ulcers from other causes of epigastric discomfort.

Helicobacter pylori infection, present in approximately 80% of gastric ulcers and 90% of duodenal ulcers, can influence pain patterns through its inflammatory effects on gastric mucosa. The bacterium’s ability to neutralise stomach acid creates areas of chronic inflammation that may produce persistent, gnawing epigastric pain even between meals.

Gallbladder pathology: cholecystitis and biliary colic patterns

Gallbladder disease affects approximately 15% of adults, with cholecystitis and cholelithiasis representing the most common pathological processes. Biliary colic, the pain associated with gallstone movement or gallbladder contraction against an obstructed cystic duct, creates characteristic epigastric pain that radiates to the right upper quadrant and often extends to the right shoulder blade. Biliary pain typically begins within 30 minutes to two hours after consuming fatty meals, as dietary fat stimulates cholecystokinin release and gallbladder contraction.

Acute cholecystitis produces more severe and persistent epigastric pain than simple biliary colic. The inflammatory process involves the gallbladder wall, creating continuous pain rather than the intermittent cramping associated with gallstone movement. Murphy’s sign, eliciting pain during inspiration whilst palpating the right subcostal area, demonstrates the relationship between gallbladder inflammation and epigastric tenderness.

Chronic cholecystitis can produce more subtle epigastric discomfort, often described as a persistent aching sensation beneath the right costal margin. This condition may develop insidiously over months or years, with patients gradually avoiding fatty foods due to the consistent relationship between fat intake and symptom exacerbation.

Pancreatic inflammatory conditions and enzyme dysfunction

Acute pancreatitis creates some of the most severe epigastric pain encountered in clinical practice, with patients often describing the sensation as “boring through” from the abdomen to the back. This pain typically develops rapidly, reaching maximum intensity within hours and persisting for days without appropriate treatment. Pancreatic pain characteristically improves when patients lean forward or assume a foetal position, as these postures may reduce pressure on the inflamed pancreas.

The relationship between alcohol consumption and pancreatic pain varies significantly among individuals. Acute alcoholic pancreatitis typically develops 6-12 hours after heavy drinking, whilst chronic pancreatitis may produce persistent epigastric discomfort that worsens with continued alcohol use. The pain often radiates to the left upper quadrant and may be accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and systemic signs of inflammation.

Pancreatic enzyme deficiency, whether from chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic ductal obstruction, can create postprandial epigastric discomfort related to maldigestion. Patients often describe a sensation of fullness and bloating beneath the ribs, particularly after consuming protein-rich or fatty meals that require substantial pancreatic enzyme activity for proper digestion.

Gastroparesis and functional dyspepsia symptomatology

Gastroparesis, characterised by delayed gastric emptying without mechanical obstruction, affects approximately 5% of the population and can produce persistent epigastric discomfort. The condition often develops secondary to diabetes mellitus, but can also result from viral infections, medications, or idiopathic causes. Gastroparetic pain typically worsens after meals and may be accompanied by early satiety, nausea, and vomiting of undigested food.

Functional dyspepsia, one of the most common functional gastrointestinal disorders, affects up to 20% of the global population. This condition produces epigastric pain or discomfort without identifiable structural abnormalities. The pain may be described as burning, gnawing, or cramping, often fluctuating in intensity and showing complex relationships with stress, sleep patterns, and dietary factors.

Understanding functional dyspepsia requires recognising that normal gastric physiological processes can become dysregulated, creating significant symptoms despite the absence of visible pathology on standard diagnostic imaging or endoscopy.

Musculoskeletal rib cage pathologies and biomechanical dysfunction

Musculoskeletal disorders affecting the rib cage and associated structures represent a frequently overlooked yet significant cause of epigastric pain. These conditions often develop following trauma, repetitive strain, or postural abnormalities that place excessive stress on the complex network of bones, cartilages, muscles, and joints comprising the thoracic wall. The pain generated by these structures can closely mimic visceral pathology, leading to diagnostic confusion and inappropriate treatment approaches.

Costochondritis and tietze syndrome inflammatory responses

Costochondritis, inflammation of the costal cartilages connecting ribs to the sternum, represents one of the most common causes of chest wall pain. This condition typically affects the cartilages of ribs two through five, though involvement of lower cartilages can produce epigastric symptoms. Costochondral inflammation creates sharp, stabbing pain that characteristically worsens with deep breathing, coughing, or physical movement of the chest wall.

The pain pattern in costochondritis often confuses patients and healthcare providers alike, as it can closely resemble cardiac pain or upper gastrointestinal pathology. However, the reproducible nature of the pain with palpation of affected costochondral junctions helps distinguish this musculoskeletal condition from visceral causes. The inflammation typically responds well to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, though resolution may require several weeks of treatment.

Tietze syndrome, a less common variant of costochondritis, involves visible swelling of the affected costochondral junctions in addition to pain and tenderness. This condition more commonly affects younger adults and may have a more prolonged course than simple costochondritis. The swelling can persist for months even after pain resolution, creating ongoing concern for patients who may worry about more serious underlying conditions.

Intercostal neuralgia and thoracic radiculopathy

Intercostal neuralgia involves inflammation or irritation of the nerves running along the ribs, creating sharp, shooting pains that follow specific dermatomal distributions. This condition can result from viral infections such as herpes zoster, trauma, or compression from rib fractures or muscle spasms. Neuralgic pain typically presents as brief, electric shock-like sensations that may be triggered by light touch or movement.

Thoracic radiculopathy, involving compression or irritation of thoracic spinal nerve roots, can produce pain that radiates along intercostal nerve distributions to the epigastric region. This condition often results from thoracic disc herniation, vertebral compression fractures, or spinal stenosis. The pain may be accompanied by numbness or tingling along the affected dermatome, helping to distinguish it from other causes of epigastric discomfort.

The relationship between posture and intercostal nerve symptoms is particularly significant in modern society, where prolonged computer use and forward head posture can contribute to thoracic spine dysfunction. These postural abnormalities can create chronic compression of intercostal nerves, leading to persistent epigastric pain that may fluctuate with activities and position changes.

Slipping rib syndrome: hypermobility of 8th, 9th, and 10th ribs

Slipping rib syndrome, also known as floating rib syndrome, occurs when the cartilaginous attachments of ribs eight, nine, and ten become hypermobile or subluxate. These ribs, lacking direct attachment to the sternum, are particularly vulnerable to trauma or repetitive stress. Rib hypermobility can create sharp, stabbing pain beneath the costal margin that may radiate into the epigastric region.

The condition often develops following activities that place excessive stress on the lower chest wall, such as heavy lifting, contact sports, or persistent coughing. Patients frequently describe a sensation of ribs “popping out of place” or “clicking” with certain movements. The pain typically worsens with activities that involve trunk rotation or lateral bending, as these movements place additional stress on already unstable rib attachments.

Diagnosis of slipping rib syndrome often requires careful physical examination, as standard imaging studies may not reveal the subtle abnormalities in rib positioning. The “hooking maneuver,” where the examiner places fingers beneath the lower costal margin and pulls anteriorly, can reproduce the patient’s symptoms and confirm the diagnosis.

Xiphoidalgia and sternocostal joint dysfunction

Xiphoidalgia, inflammation or irritation of the xiphoid process, can produce localised epigastric pain that patients often describe as a sharp, stabbing sensation directly beneath the breastbone

. This condition can develop from trauma, inflammatory processes, or biomechanical stress affecting the xiphoid process and its surrounding attachments. The xiphoid process, being the most mobile portion of the sternum, is particularly susceptible to irritation from excessive pressure or repetitive microtrauma.

Patients with xiphoidalgia often report sharp, localised pain that worsens with forward bending, deep breathing, or direct pressure application. The condition may develop following activities such as weightlifting, rowing, or other exercises that place significant stress on the anterior chest wall. Physical examination typically reveals point tenderness over the xiphoid process, with pain reproduction upon direct palpation.

Sternocostal joint dysfunction affects the articulations between the ribs and sternum, creating pain patterns that can extend into the epigastric region. These joints, though small, play crucial roles in chest wall mechanics during respiration and upper body movement. When inflammation or mechanical dysfunction occurs, patients may experience deep, aching pain that fluctuates with breathing patterns and physical activity.

Cardiopulmonary conditions presenting with sub-costal symptoms

Cardiovascular and pulmonary pathologies can frequently manifest with epigastric pain, creating diagnostic challenges that require careful clinical evaluation. The anatomical proximity of the heart and lungs to the upper abdominal region, combined with complex patterns of referred pain, means that serious cardiopulmonary conditions may initially present with symptoms resembling gastrointestinal disorders.

Acute myocardial infarction, particularly inferior wall myocardial infarctions involving the right coronary artery, can produce epigastric pain that patients and even healthcare providers may initially attribute to gastroenterological causes. This atypical presentation occurs in approximately 30% of heart attacks, with the pain often described as burning or pressure-like sensations beneath the ribs. The vagal innervation of the inferior cardiac wall creates referred pain patterns that can closely mimic peptic ulcer disease or gastroesophageal reflux.

Pericarditis, inflammation of the membrane surrounding the heart, commonly produces sharp, stabbing chest pain that may radiate to the epigastric region. This pain characteristically worsens when lying flat and improves when sitting forward, helping to differentiate it from other causes of sub-costal discomfort. The inflammatory process can create persistent aching sensations that fluctuate with breathing and movement, often confusing the clinical picture.

Pulmonary embolism can present with epigastric pain, particularly when involving the lower lobes of the lungs. The sudden onset of sharp pain beneath the ribs, combined with shortness of breath and anxiety, requires immediate medical evaluation. Atypical presentations of pulmonary embolism may lack the classic chest pain and dyspnea, instead manifesting primarily as upper abdominal discomfort that can delay appropriate diagnosis and treatment.

Pneumonia affecting the lower lobes, especially right lower lobe pneumonia, can produce significant epigastric pain through diaphragmatic irritation and referred pain mechanisms. The inflammatory process in the lung parenchyma can stimulate phrenic nerve endings, creating pain patterns that patients perceive as originating from the upper abdomen. This presentation is particularly common in elderly patients, where classic pneumonia symptoms may be absent or subtle.

Hepatobiliary system disorders and referred pain mechanisms

The hepatobiliary system’s complex anatomical relationships create distinctive patterns of referred pain that frequently manifest in the epigastric and right subcostal regions. Understanding these pain patterns requires recognition of the intimate connections between hepatic, biliary, and pancreatic structures, as well as their shared innervation through the celiac plexus and sympathetic nervous system.

Hepatitis, whether viral, autoimmune, or toxic in origin, commonly produces right upper quadrant pain that extends across the epigastric region. The liver’s substantial size means that inflammatory processes can create significant capsular distension, leading to the characteristic dull, aching sensation beneath the right costal margin. Acute hepatitis often produces more severe pain than chronic forms, with patients describing a constant heaviness or pressure that worsens with movement or deep inspiration.

Choledocholithiasis, the presence of gallstones within the common bile duct, creates particularly severe epigastric pain that may radiate to the back and right shoulder. This condition often produces Charcot’s triad: fever, jaundice, and right upper quadrant pain, though complete presentation occurs in only 50-75% of cases. The pain typically develops suddenly and may persist for hours, distinguishing it from the more transient discomfort associated with simple gallbladder contractions.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis and other biliary strictures can produce chronic, intermittent epigastric pain that fluctuates with bile flow dynamics. These conditions often develop insidiously, with patients experiencing gradually worsening pain over months or years. The inflammatory process affecting bile ducts creates complex pain patterns that may be accompanied by fatigue, pruritus, and progressive jaundice.

Hepatic congestion, whether from right heart failure or hepatic vein obstruction, can produce significant epigastric discomfort through liver capsule distension. This pain often has a throbbing quality that correlates with cardiac rhythm, helping to distinguish it from other hepatobiliary conditions. Congestive hepatopathy may also produce associated symptoms of fluid retention and exercise intolerance that provide diagnostic clues.

Biliary dyskinesia, functional gallbladder disorder characterised by abnormal gallbladder motility, can produce classic biliary pain patterns despite the absence of gallstones. This condition affects up to 8% of the population and often requires specialised testing such as cholecystokinetic cholescintigraphy for diagnosis. The pain typically follows fatty meal consumption and may be accompanied by nausea and bloating.

Advanced diagnostic approaches and differential diagnosis protocols

Accurate diagnosis of epigastric pain requires a systematic approach that considers the complex anatomical relationships and diverse pathological processes affecting this region. Modern diagnostic techniques, combined with careful clinical assessment, enable healthcare providers to distinguish between benign conditions and serious pathology that may require urgent intervention.

Initial evaluation begins with comprehensive history-taking that explores pain characteristics, temporal patterns, associated symptoms, and potential triggers. The quality of pain—whether burning, stabbing, cramping, or aching—provides valuable diagnostic clues. Temporal relationships to meals, position changes, and physical activities help narrow the differential diagnosis significantly. For instance, pain that consistently occurs 2-4 hours after eating suggests duodenal ulcer disease, whilst immediate post-prandial pain more commonly indicates gastric pathology.

Physical examination techniques specific to epigastric pain assessment include Murphy’s sign for gallbladder disease, palpation for epigastric masses or organomegaly, and assessment of abdominal tenderness patterns. The hooking maneuver for detecting slipping rib syndrome and evaluation of chest wall movement during respiration help identify musculoskeletal causes. Careful attention to vital signs, particularly blood pressure and heart rate responses to position changes, can reveal cardiovascular contributions to the pain syndrome.

Laboratory investigations play crucial roles in differential diagnosis, with specific tests tailored to clinical suspicion. Hepatic function panels assess liver enzyme elevation patterns that may indicate hepatocellular versus cholestatic pathology. Lipase and amylase levels help evaluate pancreatic involvement, though normal values do not exclude chronic pancreatic conditions. Inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate provide insights into systemic inflammatory processes.

Advanced imaging modalities have revolutionised epigastric pain evaluation, enabling visualisation of structural abnormalities and functional disorders. Computed tomography with intravenous contrast provides excellent visualisation of pancreatic morphology and can detect acute pancreatitis, masses, or vascular complications. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography offers superior visualisation of biliary and pancreatic ductal systems without ionising radiation exposure, making it particularly valuable for younger patients or those requiring repeated imaging.

Endoscopic procedures, including upper endoscopy and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, allow direct visualisation and therapeutic intervention for many conditions causing epigastric pain. Upper endoscopy enables identification and treatment of peptic ulcer disease, erosive esophagitis, and gastric pathology. ERCP provides both diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities for biliary and pancreatic ductal disorders, though its use requires careful risk-benefit analysis due to potential complications.

Functional testing approaches, such as gastric emptying studies and hepatobiliary scintigraphy, help evaluate physiological processes that may not be apparent on structural imaging. These studies are particularly valuable for diagnosing gastroparesis, biliary dyskinesia, and other functional disorders that can produce significant symptoms despite normal anatomical appearance. Provocative testing with cholecystokinin or other agents can reproduce symptoms and confirm functional diagnoses.

The integration of clinical findings, laboratory results, and imaging studies requires careful consideration of patient-specific factors including age, comorbidities, and risk factors for specific conditions. Elderly patients may present with atypical symptoms that complicate diagnosis, whilst younger patients are more likely to have functional disorders or musculoskeletal causes. The presence of alarm symptoms such as weight loss, bleeding, or progressive pain intensification necessitates more aggressive diagnostic evaluation to exclude malignancy or other serious pathology.

Multidisciplinary approaches often prove most effective for complex cases where initial evaluation fails to establish a clear diagnosis. Collaboration between gastroenterologists, hepatobiliary surgeons, cardiologists, and pain management specialists can provide comprehensive evaluation and treatment planning. This team-based approach is particularly valuable for patients with chronic epigastric pain where multiple contributing factors may be present simultaneously.