Focal intestinal metaplasia represents a significant pathological transformation occurring in gastric epithelium, characterised by the replacement of normal gastric mucosa with intestinal-type epithelium. While Helicobacter pylori infection remains the predominant aetiological factor in most cases, a substantial subset of patients develops intestinal metaplasia in the absence of this bacterium. This H. pylori-negative intestinal metaplasia presents unique diagnostic challenges and requires careful evaluation to understand its underlying mechanisms and clinical implications.

The occurrence of intestinal metaplasia without H. pylori infection has garnered increasing attention from gastroenterologists and pathologists worldwide. Recent epidemiological studies suggest that approximately 15-20% of intestinal metaplasia cases occur independently of H. pylori colonisation, indicating alternative pathogenic pathways that warrant thorough investigation. Understanding these mechanisms becomes crucial for developing appropriate surveillance strategies and therapeutic interventions.

Pathophysiology of focal intestinal metaplasia in H. pylori-negative gastric mucosa

Molecular mechanisms of gastric epithelial transdifferentiation

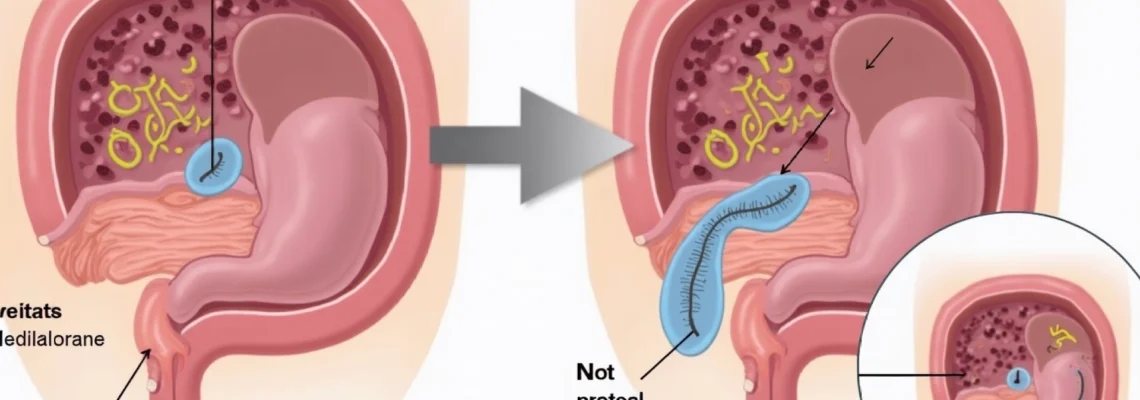

The molecular basis of H. pylori-independent intestinal metaplasia involves complex transcriptional reprogramming that fundamentally alters gastric epithelial cell identity. This transformation occurs through a process called transdifferentiation , where mature gastric epithelial cells acquire intestinal characteristics without reverting to a stem cell state. The process involves the activation of specific transcription factor networks that normally govern intestinal development.

Key molecular players include the Wnt signalling pathway, which becomes dysregulated in the absence of H. pylori-mediated inflammation. This pathway activation leads to the expression of intestinal-specific genes while simultaneously suppressing gastric-specific transcriptional programmes. The transformation typically begins in the deep gastric glands and progressively extends toward the surface epithelium, creating the characteristic focal pattern observed histologically.

CDX2 and SOX2 transcription factor expression patterns

The balance between CDX2 and SOX2 transcription factors plays a pivotal role in determining gastric versus intestinal cell fate. In H. pylori-negative intestinal metaplasia, CDX2 expression becomes aberrantly activated through mechanisms independent of bacterial-induced inflammation. This homeobox transcription factor directly regulates intestinal-specific genes including MUC2, villin, and alkaline phosphatase.

Conversely, SOX2 expression, which maintains gastric epithelial identity, becomes progressively downregulated in metaplastic areas. This reciprocal relationship creates distinct molecular boundaries within the gastric mucosa, with SOX2-positive regions retaining gastric characteristics whilst CDX2-positive areas exhibit intestinal phenotypes. The spatial distribution of these transcription factors often correlates with the extent and severity of metaplastic transformation.

Chronic Gastritis-Independent metaplastic transformation

Unlike H. pylori-associated intestinal metaplasia, which typically occurs within a background of chronic active gastritis, H. pylori-negative cases may develop in relatively normal gastric mucosa. This observation suggests that chronic inflammation, whilst facilitating metaplastic transformation, is not an absolute prerequisite for its development. Alternative triggers include oxidative stress, genetic predisposition, and environmental factors that can initiate the transdifferentiation process.

The absence of significant inflammatory infiltrate in many H. pylori-negative cases indicates that different molecular pathways drive the metaplastic process. These may include age-related cellular senescence, telomere dysfunction, or exposure to specific chemical carcinogens that directly affect epithelial cell programming without necessarily inducing substantial inflammatory responses.

Bile acid reflux and duodenogastric reflux disease contributions

Duodenogastric reflux represents a significant aetiological factor in H. pylori-negative intestinal metaplasia development. Bile acids , particularly deoxycholic acid and lithocholic acid, can directly induce CDX2 expression in gastric epithelial cells through nuclear receptor activation. This mechanism explains why intestinal metaplasia frequently occurs in the gastric antrum, where bile acid exposure is most pronounced.

The cytotoxic effects of bile acids create chronic epithelial damage that triggers adaptive responses leading to intestinal differentiation. This process occurs independently of H. pylori infection and may be particularly relevant in patients with pyloric dysfunction, previous gastric surgery, or gastroesophageal reflux disease. The temporal relationship between bile reflux episodes and metaplastic development suggests a dose-dependent effect of bile acid exposure.

Histopathological classification systems for H. pylori-independent intestinal metaplasia

Complete vs incomplete metaplasia phenotypes in Non-Infectious cases

The classification of intestinal metaplasia into complete and incomplete subtypes holds particular significance in H. pylori-negative cases, as the distribution patterns and progression risks differ from infection-associated metaplasia. Complete intestinal metaplasia in H. pylori-negative patients typically exhibits well-formed goblet cells with preserved mucin production and distinct brush border formation. These areas closely resemble normal small intestinal epithelium with characteristic absorptive enterocytes.

Incomplete intestinal metaplasia in non-infectious cases demonstrates more heterogeneous cellular populations with mixed gastric and intestinal features. The presence of intermediate cell types suggests ongoing transdifferentiation processes that may be more amenable to intervention than fully established complete metaplasia. This subtype often shows greater proliferative activity and may carry increased malignant potential.

The spatial distribution of complete versus incomplete metaplasia in H. pylori-negative cases tends to be more focal and localised compared to the extensive, multifocal pattern typically seen with H. pylori infection. This distribution pattern has important implications for biopsy sampling strategies and surveillance protocols.

Goblet cell morphology and mucin expression analysis

Goblet cell morphology serves as a crucial diagnostic criterion for distinguishing H. pylori-negative intestinal metaplasia from reactive gastric changes. In true intestinal metaplasia, goblet cells display characteristic features including apical mucin droplets, compressed nuclei, and well-defined cell boundaries. The mucin composition differs significantly between complete and incomplete subtypes, with complete metaplasia producing predominantly acidic mucins similar to normal intestinal goblet cells.

Morphometric analysis reveals that goblet cell density and distribution patterns in H. pylori-negative cases often show greater uniformity compared to infection-associated metaplasia. This finding suggests more organised transdifferentiation processes occurring in the absence of inflammatory disruption. The preservation of goblet cell polarity and mucin secretion patterns indicates maintained epithelial barrier function in many non-infectious cases.

Sydney system classification modifications for H. pylori-negative specimens

The Sydney System classification requires modification when applied to H. pylori-negative intestinal metaplasia cases, as the traditional scoring parameters emphasise inflammatory components that may be minimal or absent. Modified scoring systems focus on architectural distortion, epithelial atypia, and the extent of metaplastic transformation rather than inflammatory activity.

These modifications include assessment of glandular architecture preservation, surface epithelial integrity, and the presence of transitional zones between gastric and intestinal phenotypes. The absence of significant inflammation necessitates greater reliance on morphological features and immunohistochemical markers to accurately grade the severity and extent of metaplastic changes.

Immunohistochemical markers: MUC2, MUC5AC, and MUC6 expression profiles

Immunohistochemical analysis of mucin expression patterns provides essential diagnostic information for characterising H. pylori-negative intestinal metaplasia. MUC2 expression represents the most specific marker for intestinal differentiation, typically showing strong positivity in goblet cells of both complete and incomplete metaplasia subtypes. The intensity and distribution of MUC2 staining correlates with the degree of intestinal transformation.

MUC5AC expression patterns help distinguish between different metaplasia subtypes, with complete metaplasia showing reduced or absent expression whilst incomplete subtypes may retain variable positivity. MUC6 expression, normally present in gastric mucous neck cells, becomes progressively lost as metaplastic transformation advances. The combination of these markers provides a molecular fingerprint that aids in classification and prognosis assessment.

The immunohistochemical profile MUC2+/MUC5AC-/MUC6- characterises mature complete intestinal metaplasia, whilst the profile MUC2+/MUC5AC+/MUC6+/- suggests incomplete metaplasia with retained gastric features.

Non-helicobacter aetiological factors in focal gastric intestinal metaplasia

Autoimmune gastritis and pernicious anaemia associations

Autoimmune gastritis represents a significant cause of H. pylori-negative intestinal metaplasia, particularly affecting the gastric body and fundus. This condition involves immune-mediated destruction of parietal cells, leading to achlorhydria and subsequent epithelial changes. The resulting hypergastrinaemia creates a growth-promoting environment that facilitates intestinal metaplasia development through trophic effects on gastric epithelium.

Patients with pernicious anaemia demonstrate particularly high rates of intestinal metaplasia development, with studies indicating prevalence rates exceeding 60% in established cases. The metaplastic transformation typically occurs in areas of severe atrophic gastritis where parietal cell loss is most pronounced. Anti-parietal cell antibodies and anti-intrinsic factor antibodies serve as valuable serological markers for identifying patients at risk.

The progression from autoimmune gastritis to intestinal metaplasia follows a predictable temporal pattern, with initial parietal cell destruction preceding metaplastic transformation by several years. This timeline provides opportunities for early intervention and surveillance in at-risk patients. The extent of intestinal metaplasia in autoimmune gastritis correlates with disease duration and severity of gastric atrophy.

Environmental carcinogen exposure and dietary nitrosamine compounds

Environmental carcinogen exposure plays a crucial role in H. pylori-independent intestinal metaplasia development, particularly through dietary sources of nitrosamine compounds and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. These substances can directly induce DNA damage and epigenetic modifications that promote cellular transformation. Nitrosamine compounds , formed through nitrite and amine interactions in processed foods, demonstrate particular potency in inducing gastric epithelial changes.

Occupational exposures to industrial chemicals, heavy metals, and organic solvents have been associated with increased intestinal metaplasia risk in several epidemiological studies. The latency period between exposure and metaplasia development varies considerably, ranging from months to decades depending on exposure intensity and individual susceptibility factors. Geographic clustering of cases often reflects local environmental contamination patterns.

Dietary factors beyond carcinogen exposure also influence metaplasia development, with high-salt diets, low antioxidant intake, and inadequate fresh fruit and vegetable consumption all contributing to increased risk. The protective effects of dietary antioxidants, particularly vitamin C and beta-carotene, appear to operate through neutralisation of reactive oxygen species that would otherwise promote cellular transformation.

Genetic polymorphisms in IL-1β and TNF-α gene clusters

Genetic polymorphisms affecting cytokine production significantly influence susceptibility to H. pylori-negative intestinal metaplasia development. Polymorphisms in the IL-1β gene cluster , particularly the IL-1β-511 C/T variant, affect inflammatory response patterns and tissue repair mechanisms even in the absence of bacterial infection. These genetic variations can predispose individuals to excessive inflammatory responses to minor gastric irritants.

TNF-α polymorphisms, especially the TNF-α-308 G/A variant, influence tumour necrosis factor production and subsequent epithelial cell survival responses. Individuals carrying high-expression alleles demonstrate increased susceptibility to intestinal metaplasia development when exposed to environmental triggers. The interaction between genetic predisposition and environmental factors follows a multiplicative rather than additive risk model.

Recent genome-wide association studies have identified additional susceptibility loci affecting gastric epithelial homeostasis and DNA repair mechanisms. These findings suggest that H. pylori-negative intestinal metaplasia results from complex gene-environment interactions that vary considerably between populations and geographic regions.

Epstein-barr virus and cytomegalovirus Co-Infections

Viral infections, particularly Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and cytomegalovirus (CMV), have emerged as potential aetiological factors in H. pylori-negative intestinal metaplasia development. EBV infection can establish latent infection in gastric epithelial cells, leading to chronic immune stimulation and cellular transformation. The viral proteins expressed during latent infection interfere with normal epithelial differentiation programmes.

CMV infection demonstrates particular tropism for gastric mucosa in immunocompromised patients, where it can cause chronic ulceration and subsequent metaplastic healing responses. The viral-induced cytopathic effects create tissue damage that triggers reparative processes involving intestinal differentiation pathways. Co-infection with multiple viruses appears to synergistically increase metaplasia risk.

The temporal relationship between viral infection and metaplasia development varies considerably, with some cases developing within months of acute infection whilst others require years of chronic viral persistence. Antiviral therapy in selected cases has demonstrated potential for preventing progression, though optimal treatment strategies remain under investigation.

Diagnostic protocols for H. pylori-negative intestinal metaplasia detection

Accurate diagnosis of H. pylori-negative intestinal metaplasia requires comprehensive evaluation incorporating multiple diagnostic modalities. The diagnostic approach must exclude H. pylori infection through multiple testing methods whilst simultaneously identifying alternative aetiological factors. Initial assessment should include detailed clinical history focusing on medication use, dietary habits, family history of gastric diseases, and previous gastric procedures.

Endoscopic evaluation plays a crucial role in identifying metaplastic areas, which may appear as pale, slightly elevated patches with altered vascular patterns. High-definition endoscopy with narrow-band imaging enhances detection sensitivity by highlighting architectural changes and vascular abnormalities associated with intestinal transformation. The Sydney protocol for biopsy sampling should be followed, with additional targeted biopsies from suspicious areas.

Laboratory investigations must comprehensively exclude H. pylori infection using multiple methods including histology, rapid urease testing, culture, and serology. The combination of negative histology and negative serology provides the highest confidence in H. pylori-negative status. Additional testing should include assessment for autoimmune markers, vitamin B12 levels, and gastrin concentrations when autoimmune gastritis is suspected.

The diagnosis of H. pylori-negative intestinal metaplasia requires exclusion of current and previous H. pylori infection through multiple testing modalities, as relying on a single negative test may lead to misclassification.

Histopathological examination remains the gold standard for diagnosing intestinal metaplasia, requiring experienced pathologists familiar with the morphological variants seen in H. pylori-negative cases. Special stains including Alcian blue-PAS and immunohistochemical markers for CDX2, MUC2, and Ki-67 provide additional diagnostic information. The assessment should include evaluation of background gastric mucosa for evidence of chronic inflammation, atrophy, and dysplasia.

Clinical surveillance strategies and malignant progression risk assessment

The surveillance strategy for H. pylori-negative intestinal metaplasia requires individualised risk assessment considering multiple factors including metaplasia extent, histological subtype, patient age, and family history. Risk stratification should classify patients into low, intermediate, and high-risk categories based on validated scoring systems that incorporate both histological and clinical parameters. This stratified approach optimises surveillance intervals whilst minimising unnecessary procedures.

Current evidence suggests that H. pylori-negative intestinal metaplasia may carry a different risk profile compared to infection-associated cases, with some studies indicating lower progression rates to high-grade dysplasia and carcinoma. However, certain subtypes, particularly extensive incomplete metaplasia or cases associated with autoimmune gastritis, may warrant more intensive surveillance. The optimal surveillance interval remains under investigation, with most guidelines recommending 3-year intervals for high-risk cases.

| Risk |

|---|

Advanced endoscopic techniques including magnification endoscopy and chromoendoscopy may enhance detection of subtle dysplastic changes during surveillance procedures. These technologies allow for targeted biopsies of suspicious areas and may improve the sensitivity of surveillance protocols. The integration of artificial intelligence algorithms for real-time polyp and dysplasia detection represents an emerging frontier that could standardise surveillance quality across different centres.

Biomarker development for risk stratification remains an active area of research, with serum pepsinogen ratios, gastrin-17 levels, and methylation markers showing promise for non-invasive surveillance approaches. These biomarkers could potentially identify patients at highest risk for progression, allowing for more personalised surveillance strategies whilst reducing the burden of repeated endoscopic procedures for low-risk patients.

Therapeutic interventions for non-infectious gastric intestinal metaplasia management

Management of H. pylori-negative intestinal metaplasia focuses primarily on addressing underlying aetiological factors and implementing strategies to prevent malignant progression. Proton pump inhibitor therapy remains controversial in this context, as while it may reduce acid-mediated mucosal damage, long-term use has been associated with progression of atrophic changes and potential bacterial overgrowth that could complicate the clinical picture.

For patients with autoimmune gastritis, vitamin B12 supplementation represents essential therapy to prevent pernicious anaemia and its associated complications. Iron supplementation may also be necessary in cases with concurrent iron deficiency anaemia. Regular monitoring of vitamin levels and haematological parameters ensures appropriate dosing and identifies developing deficiencies before clinical symptoms manifest.

Dietary modifications play a crucial role in managing H. pylori-negative intestinal metaplasia, particularly reducing exposure to dietary carcinogens and increasing protective antioxidant intake. Patients should be counselled to limit processed meat consumption, reduce salt intake, and increase consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables rich in vitamin C and beta-carotene. Antioxidant supplementation with vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium has shown potential benefits in some studies, though optimal dosing protocols remain under investigation.

Bile acid sequestrants may benefit patients with documented duodenogastric reflux, helping to reduce bile acid exposure to the gastric mucosa. Ursodeoxycholic acid has demonstrated cytoprotective effects in preliminary studies and may help prevent further metaplastic progression. However, the evidence base for these interventions remains limited, and treatment decisions should be individualised based on patient-specific factors and response to therapy.

Chemoprevention strategies using cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, aspirin, or other anti-inflammatory agents have shown promise in experimental models but require careful risk-benefit assessment in clinical practice. The potential cardiovascular and gastrointestinal risks of long-term anti-inflammatory therapy must be weighed against uncertain benefits for metaplasia regression. Current evidence does not support routine chemoprevention outside of clinical trial settings.

Emerging therapeutic approaches include the use of probiotics to modulate gastric microbiota and reduce inflammatory responses, though specific strains and dosing regimens for H. pylori-negative intestinal metaplasia require further investigation. Curcumin and other natural compounds with anti-inflammatory properties have demonstrated preclinical efficacy but need validation in human studies before clinical implementation.

The management of H. pylori-negative intestinal metaplasia requires a multidisciplinary approach combining surveillance protocols, lifestyle modifications, and targeted interventions based on underlying aetiological factors.

Recent advances in regenerative medicine have explored the potential for reversing intestinal metaplasia through stem cell therapy and tissue engineering approaches. While these interventions remain experimental, early results suggest that gastric epithelial regeneration may be possible under specific conditions. The development of organoid culture systems has provided new insights into the cellular mechanisms underlying metaplastic transformation and potential reversal strategies.

Patient education represents a fundamental component of management, ensuring individuals understand their condition, the importance of surveillance, and modifiable risk factors. Regular follow-up consultations should address dietary compliance, symptom development, and psychosocial impacts of living with a premalignant condition. The involvement of specialist nurses and dietitians can enhance patient support and improve adherence to recommended interventions.

Future therapeutic developments may include targeted molecular therapies aimed at reversing CDX2 expression or promoting SOX2 re-expression in metaplastic areas. Gene therapy approaches and epigenetic modulators represent exciting possibilities for directly addressing the molecular basis of intestinal metaplasia. However, these interventions require extensive safety testing and efficacy validation before clinical application becomes feasible.